Concerto (In the Form of Variations) for Viola and Orchestra

Instrumentation

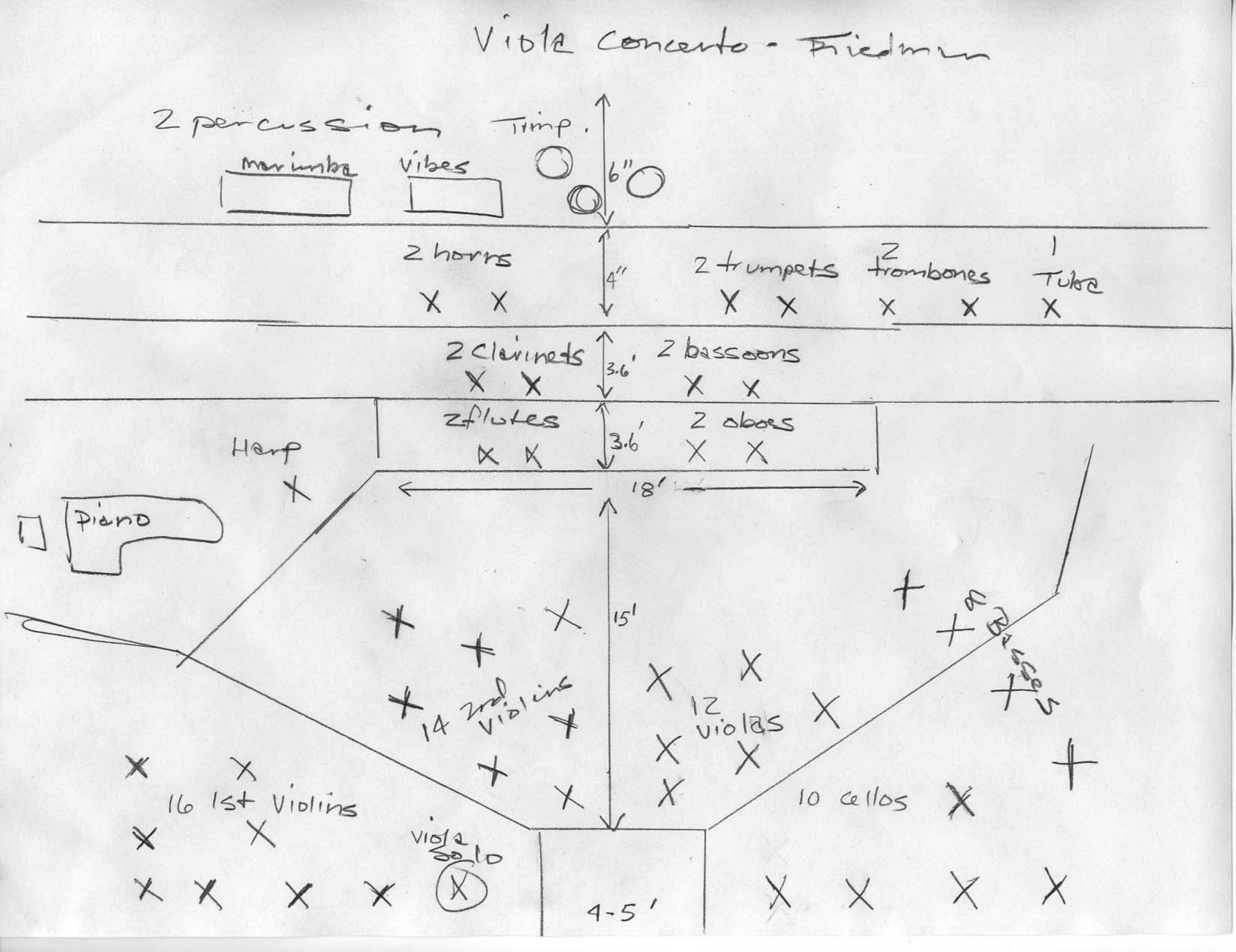

2(II=picc.).2.2(II=bcl).2-2.2.2.1-hp-pft*-2perc**-strings * some light preparation is necessary (see score for details) ** I = lg susp.cym, high tam-t, TB, crot (w/bow), vib, BD, SD; II = lg susp.cym, low tam-t, BD, timp; to be shared (I&II)= 2 timb, 3 tom-t, mar

This concerto offers a window into two very important moments in my life. The heavy moment is I was processing my father’s suicide a little over two decades before as I composed the piece. On a happier note, this is how I met my wife, Jenny BIlfield. After her panel of judges picked my concerto, and after conductor Jorge Mester selected it for Carnegie Hall, Jenny and I became friends. You could say it was my “viola in my life” moment (Hat tip to Morton Feldman). Premiered by violist Paul Neubauer at Carnegie Hall, this dramatic, single-movement concerto is a theme and four variations, and was described by Andrew Porter in The New Yorker as “…a poetic, beautiful, and intelligent exploration of a long, eloquent melody, through variations that are at first musing and gentle, then passionate, finally simple, confident, and serene. The work is a dramatic scena for the soloist; the orchestra provides at once a setting and a cast of conversants and commentators.” For my work I received the 1988 ASCAP Young Composers’ Competition Award (now The ASCAP Foundation Morton Gould Young Composer Award) and was one of the winners of the 1989 New Music Orchestral Project competition (sponsored by the National Orchestral Association).

Program Note

As its title suggests, the Concerto (in the Form of Variations) combines two “old and venerable forms,” as the composer calls them. The work’s three-part structure (slow-fast-slow) suggests a multi-movement concerto, while its theme and four variations bind the work into a single whole. “The fun came in combining the two forms,” Friedman explains.

“Theme and variations have always held a fascination for me. There is a real beauty and elegance to the form. They also present a challenge: imagine creating a complete musical world out of a tiny fragment (the theme). For me, the form represents a beautiful paradigm for trying to understand the world. While one can try to learn a little bit about everything — survey the surroundings — it’s also possible to focus on only a tiny corner and exhaustively explore every inch of it’s terrain. For me composing variations is an example of the later.” Like many sets of variations, the concerto is extremely organic for all of its diversity. It is woven from only a few musical ideas: a thematic shape fashioned from a descending semitone followed by a rising minor seventh; a characteristic harmonic interval of a minor sixth; and a distinctive rhythm – q. q. iq (long, long, short-short) – that permeates the work.

The tension between soloist and orchestra places the work in the tradition of classical concertos. According to the composer, “My mind works best when confronted with a dramatic situation, where there are ‘characters’ involved . . . The concerto has always been thought of as a highly dramatic form with inherent theatrical possibilities. Mozart’s concertos are often like instrumental operas.”

The dramatic nature of Friedman’s concerto is hardly surprising, since he is a theatrical and opera, as well as a symphonic composer. He is co-author of the musical Personals, which was voted one of the ten best shows of 1985. One of the longest running shows on or off Broadway, Personals was nominated for four Outer Critics Circle Awards (winning one) and four Drama Desk Awards, including Best Score and Best Musical.

The Concerto begins with a cadenza that features the solo instrument over a rhythmic foil of piano, harp, and percussion. The theme is foreshadowed by this atmospheric passage. The accompaniment is fashioned from canons based upon the previously mentioned long-long-short-short rhythm, while the viola, which moves from its lowest register up to “viola stratosphere,” introduces thematic and harmonic cells. Knowing virtuoso violist Paul Neubauer would premiere the work gave Friedman the confidence to explore the extreme upper range of the instrument in dramatic fashion.

In a subtle formal twist, the theme for this set of variations is not introduced by “the star,” the viola soloist, but by the violins and clarinet. The viola is busy with an obbligato melody that “serenely floats above the fray.” This obbligato line eventually descends, dovetailing into and then taking over the theme at its midpoint. After the exposition of the theme comes the first variation, “A Theme and its Shadow.” As the viola plays an embellished version of the new main melody an assortment of lower registered instruments simultaneously present a slower, emotionally detached version of this same theme. “Both seem to go on their own way without realizing that the other is there,” says Friedman A quizzically disquieting muted descending figure in the strings periodically interrupts the flow of the variation only to come to fruition as it coalesces into a loud orchestral outburst near the end of the variation.

The second variation is in two parts: “a muted section of suppressed yearning, and a broader lyrical pastorale.” An extension of the pastorale materials serves as a transition to the climax of the work, the third variation. The aggressive, syncopated third variation (“Ritmico”) is a transformation of the previous variation. The driving rhythms are briefly interrupted by a whimsical, yet sardonic contrasting section that features the viola and the piccolo in a duet before the faster, motoric material returns. After a surging climax, a second cadenza that recalls both the concerto’s opening and the original theme leads to the serene final variation (“Chorale”). It is as if all superfluous elements have been burned off the theme by the work’s previous struggles leaving a slow, luminous chorale that the composer describes as “simplicity itself.”

Jonathan D. Kramer and Joel Phillip Friedman

(Adapted from Jonathan Kramer’s original Carnegie Hall program note)

Listen

Score Preview

Reviews

“…a poetic, beautiful, and intelligent exploration of a long, eloquent melody, through variations that are at first musing and gentle, then passionate, finally simple, confident, and serene. The work is a dramatic scena for the soloist; the orchestra provides at once a setting and a cast of conversants and commentators.” Andrew Porter, The New Yorker

“The program took a distinct upswing when Paul Neubauer soloed in the longest and by far best work on the program: Joel Phillip Friedman’s Concerto for Viola and Orchestra. This is a magnificent work of tremendous expressive force, often poignant and threnodic, yet always inspiring in its fecundity of ideas and assured development.” Bill Zakariasen, Daily News

“The scoring for solo viola is brilliant…” James R. Oestreich, The New York Times

“…the viola sang a mournful, rich melody that the orchestra generally accompanied and underscored. It was a genuine concerto, giving a prominent, virtuoso role to the viola…” Peter Goodman, Newsday

“The Concerto is a magnificent, twenty-minute viola declamation: dramatic, passionate, lyrical, eloquent, acerbic, tender, rough, sentimental, and yet pleasant and approachable by twentieth century standards. It is a completely qualified candidate to be programmed by a good orchestra and mature soloist as a serious part of a subscription-series concert.

…the overall impression is of originality…The concerto is masterly constructed, doubtless with compositional complexities, contrapuntal cunning, and clever connivances enough to keep the high-minded occupied as long as they want to be…Mr. Friedman really does know how to put what he wants on paper…his orchestration is meticulous, reminiscent of Tchaikovsky or Mahler in attention to detail.

The solo part is for a virtuoso, and Mr. Neubauer certainly is one of our finest. The soloist is allowed to show the best side of our instrument, and without having to compete overly with the orchestral forces.

All in all, this is a splendid addition to the repertory. One can only hope that it will not languish in obscurity, since it is so attractive and practical.” Thomas G. Hall, Journal of the American Viola Society